What’s not to love about Egyptian hieroglyphics and figure art? Fascinating characters with animal heads… mysterious drama… even a form of writing that is fun to look at. Egyptian art is remarkable for many reasons. There’s always an interesting narrative, and it’s almost always done in that elegant Egyptian style – something that lasted throughout the ages.

So, clearly there’s a story here. Something important is happening. It’s really a storybook, and there’s nice descriptive text to accompany the images. Of course, most of us can’t read it, but the good news is, someone can. So what’s going on in this illustrated story? Answers below…

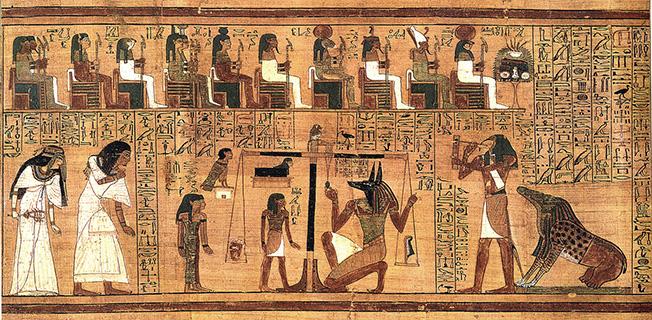

Papyrus of Ani: Weighing of the heart of the scribe Ani

(click here to see a larger image in a new window)

c1250 BCE

On a piece of reed paper called “papyrus”, part of what was originally a 78 foot scroll (cut apart by the discoverer).

Egypt (now in the British Museum)

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The ancient Egyptians had elaborate and complicated funereal practices. The Papyrus of Ani was a scroll created to help a deceased man named Ani to enter the afterlife. Called a “Book of Going Forth by Day,” the scroll had a wealth of information about what Mr. Ani would encounter on his journey into the hereafter. This panel of the scroll depicts (reading left to right):

- Overall, the scene depicts the weighing of Ani’s heart – a mystical act that will determine if he is allowed to proceed into the afterlife. It is weighed against a thing called the feather of Maat – a feather that embodies the ideas of truth, balance, order, law, morality, and justice. These ideas are also associated with the Egypitan goddess, Maat.

- At left, Ani and his wife, clad in white, enter the judgement area.

- The contraption in the middle is the balance scale used for weighing the heart. You can see Ani’s heart on one side and the feather on the other. The dog headed fellow is Anubis, the god of embalming.

- The process is observed by a representation Ani’s soul called his ba. That’s the bird-like creature perched on the wall.

- The ibis-headed god, Thoth, stands to the right of the scales, ready to record what happens.

- And right behind him is a crocodile-leopard-hippo creature (a CrocoLeoPo?), that is a “devourer” who will eat the heart if Ani does not measure up, thereby dooming him to oblivion (the Egyptians did not believe in a Heaven/Hell arrangement).

- At the top is the pantheon of Egyptian gods, overseeing the process. Serious business.

The papyrus the Egyptians uses to write on (they didn’t have paper as we know it today), was made from the papyrus plant – a reed. It was not an overly complicated process, but resulted in a material that has held up over centuries (the dry air helped). Here’s a nice slide show, from the University of Michigan Library, on how papyrus was made.

The stylized look of Egyptian figures comes, in part, from the fact that had not developed the use of perspective in art (or chose not to use it?). And, it comes from their use of art as a symbolic, storytelling medium. They were not interested in depicting real three dimensional space with accurate sizes of one figure to another. They developed a “Canon of Proportions” that laid out how to represent figures. It was based on the width of the fist, measured across the knuckles, with 18 fists from the ground to the hairline on the forehead. There were stylistic conventions as well: Figures were always depicted in a flat view that is a mixture of profile (face) and frontal (shoulders). It was really like a language of set poses. Ancient Egyptian social structure was highly stratified, and the class of artisans – paid and under the control of the state – would have been well versed in the conventions of how to make proper art.